[fusion_dropcap]L[/fusion_dropcap]actose is the sugar molecule found in milk. It is digested by the enzyme lactase that is secreted by intestinal cells. Lactase activity is highest immediately after birth so infants can digest milk appropriately, but in the majority of people lactase activity declines dramatically during childhood and adolescence to about five to ten percent of the activity at birth. Only a small percentage of people (approximately thirty percent) retain enough lactase to digest and absorb lactose efficiently throughout adulthood. Lactase deficiency may also develop when intestinal cells are damaged by disease (e.g. coeliac disease), surgery, prolonged diarrhoea or malnutrition. A decline in lactase activity can lead to poor digestion of lactose, otherwise called lactose intolerance. When more lactose is consumed than the available lactase can digest, the lactose molecules remain in the digestive system undigested and attract water. This causes bloating, abdominal discomfort and diarrhoea that may or may not be frothy.

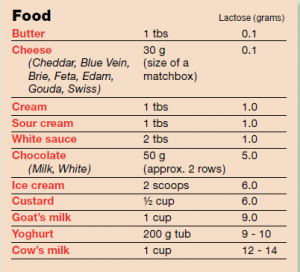

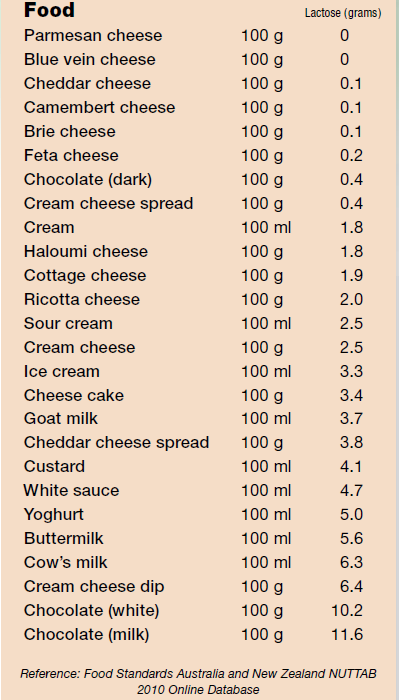

The undigested lactose also becomes food for intestinal bacteria, which multiply and produce gas which leads to flatulence. These symptoms usually begin between thirty minutes and two hours after consumption of dairy foods, and the severity of symptoms depends on the quantity of lactose that was ingested, and how much lactase activity remains within the digestive system of the individual. I have put together the following table, which illustrates the different amounts of lactose in a range of dairy products from lowest to highest per 100 grams or 100 millilitres of food: From this table we can see that some cheeses (Parmesan,blue vein, cheddar, camembert, brie and feta ) and dark chocolate have no or very low levels of lactose, whereas buttermilk, cow’s milk, dips made from cream cheese and both white and milk chocolate contain a much greater quantity of lactose. Generally speaking, people who are lactose intolerant can still tolerate some lactose, usually up to twelve grams of lactose per day or up to four grams per meal. More than this may lead to the abdominal symptoms outlined previously. However, please note that lactose intolerance is not a serious threat to health, and can be managed via dietary modification. We don’t always consume 100 grams or 100 millilitres of a food, so the following table shows the lactose content of everyday serving sizes of common dairy foods:

Therefore, if you are lactose intolerant, it is advisable

to avoid large quantities of:

- milk and all milk-based products (unless they are lactose free)

- cream, sour cream, crème fraiche

- most kinds of yoghurt (some very acidic yoghurts tend to contain less lactose because the bacteria in the yoghurt help to digest the lactose)

- cottage cheese and cheese spreads (hard, aged forms of cheese, such as parmesan and cheddar, contain very low levels of lactose so they may be tolerated)

- sauces made from milk or cream, such as white sauce, cheese sauce, etc

- quiche, frittata, flans, pancakes, custard, batter and other products containing milk

- rice and other forms of pudding made from milk products

- most home-made cakes, as they tend to contain milk (products made from butter but not milk such as biscuits,cookies and pastry are usually better tolerated)

- sheep and goat’s milk ( these contain less lactose than cow’s milk but are not lactose free )

- ice cream, as this can be particularly difficult for people with lactose intolerance to digest ( not only is the ice cream made from milk, but extra lactose is often added to improve the texture )

- packaged dessert mixes, as these tend to contain lactose

- chocolate made from milk products

- any food containing the words ‘milk solids’ or ‘non-fat milk solids’ on the product label (lactose is added to many processed foods, including breads, canned and powdered soups, cookies, pancakes mixes, powdered drink mixes such as flavoured coffee, Milo, Ovaltine, drinking chocolate, processed breakfast cereals, processed meats and salad dressings)

- lactose in medicines ( lactose powder is used in many tablets and capsules to bulk up the drug)

- lactose-based foods on an empty stomach

Milk and dairy products often provide the main source of calcium in the diet, and there is a high need for calcium in the body to keep bones strong and healthy, especially in older individuals. There can therefore be a concern about calcium intake when dairy products are removed from the diet. Some alternatives to milk and dairy products to consider are:

- lactose-reduced cow’s milk (e.g. Zymil or long-life milkthat is labelled as ‘lactose free’)

- soy, rice, oat or almond milk

- soy cheese such as Mini Chol

- soy yoghurt

- soy ice cream

- gelati

- very acidic / tart yoghurt

- chocolate made from carob

- food labelled ‘suitable for vegans’

However, there are other food sources of calcium, such as:

- almonds ( which I would recommend in small amounts in the form of almond spread as found in the health food section of most supermarkets)

- firm tofu

- apricots

- calcium-fortified orange juice ( in small amounts at a time so as not to loosen output )

- tinned salmon containing softbones

- sardines with soft bones

- spinach ( in small amounts and chewed well to avoid the risk of a blockage)

- broccoli ( cooked and eaten in small amounts or as a soup to avoid the risk of a blockage)

- dark green leafy vegetables ( in small amounts and chewed very well to avoid a blockage)

- sesame seeds ( which I recommend in the form of tahini for Ostomates )

- calcium fortified soy, oat, almond or rice milk

As always, my recommendations when extending the diet and incorporating new foods into the menu are to try a small amount at a time, eat slowly, chew food really well and wait a few days to determine the response.

Wishing you good health and happy days, Margaret.

“Source: (Ostomy Australia Magazine) Margaret Allan is a qualified Nutritionist who advises Ostomates and the general public on diet and health-related matters. Margaret is based in Melbourne and is available for clinical and telephone consultations by appointment. Margaret can be contacted via email on [email protected]”

Reproduced from Ostomy Australia, April 2015, P36-37